The Friar Haciendas

The Friar Haciendas

Even as the friars zealously propagated the Catholic faith, they never lost sight of the

temporal interests of their religious congregation. Vast tracts of land were granted by the

Spanish King to those who helped in the pacification of the land. Later, the encomiendas were

converted into the haciendas. The different religious orders who helped in subduing the natives

also received their share of arable lands which would support their various communities and

endeavors. The friars acquired their hacienda either by purchase or through gifts of pious

faithful.

On January 18, 1752, Bacoor was created as an independent parish by a Royal Cedula. It was

administered by secular clergy, Fr. Joseph Jimenez, who was also one of the earliest known

parish priests of Bacoor. San Francisco de Malabon was created as an independent parish by the

Royal Cedula of September 9, 1753. However, there are some data, which say as early as 1661

there were already secular priests assigned in the place. In 1769, the old church was

demolished, and a new one was built with the help of Doña Maria Josepha de Yrruzarri y Ursua,

Condesa de Lizarraga who had an hacienda in the town. Just like San Francisco de Malabon, Sta.

Cruz de Malabon (Tanza) was also a secular foundation. As early as 1768, a secular priest, Fr.

Antonio Flores, had been assigned as chaplain of the place.

In 1666, a few decades after the arrival of the Augustinian Recollects in the Philippines, they

began acquiring vast tracts of land. Its first acquisition was the Hacienda de San Nicolas de

Tolentino, formerly known as Hacienda de Sta. Cruz in Bacoor. On November 4, 1666, Doña Hipolita

Zarate y Ocequera donated the hacienda to the Recollect Fathers of Intramuros on condition that

masses would be said for her soul.

In the nineteenth century more parishes in Cavite were established and were administered by

secular clergy. Rosario in 1846; Carmona in 1857; Bailen in 1858; Alfonso in 1859; Mendez Nunez,

quite a strange parish for it had three days of foundation. It is said that the parish was

created on December 23, 1879. The Royal Order creating the parish was dated December 17, 1880,

while the Superior Decree Ordering the implementation of the Order for the creation of the

parish was dated February 17, 1881. On March 14, 1881, it was given to a secular priest, Fr.

Pascual Roque. However, on April 30, 1881, it was given to a Dominican, Fr. Santiago Roy. The

parish of Magallanes was created as a parish by the Royal Order of March 3, 1882, under the

administration of the secular clergy. However, the actual establishment came between 1883 and

1884.

Then on July 4, 1626, Don Juan de Oleas made a series of purchases, which culminated with his

complete ownership of the lands formerly owned by former Governor-General Santiago de Veyra and

Luis Perez Dasmariñas. When Don Juan died, Doña Maria de Roa vda. de Oleas, who inherited the

property located along the enclaves of Cavite Viejo, Binakayan, and Imus, sold her land. This

property known as San Juan del Rio, was auctioned by the Auto de la Real Audiencia on December

1, 1685. Gen. Tomas de Andaya bought the land for P12,500.00 and took possession of it on

January 18, 1686. It seemed that he was just a dummy, because on November 5 of the same year, he

transferred the ownership to the Augustinian Recollect Order.

This was followed on October 3, 1690, when the secular priest B. Don Jose de Solis, sacristan

mayor de la iglesia parroquial de Cavite Puerto, sold his property to the Recollects for the

amount of P1,500.00. This was situated at Bagong Bayan de Calompang on Sitio Camarin.

Finally, on June 12, 1812, Don Manuel Frutos Andreis of Comercio de Manila, sold his land for

P27,000.00 to the Recollect Fathers. This land acquisition completed what was used to be known

as Hacienda de Imus. The acquired total land area was 18,419 hectares, 56 areas, and 12

centiareas. Later, the Recollects reconstitute the hacienda. All the properties in the town of

Bacoor came to be known as Hacienda de San Nicolas de Tolentino, while those which comprised

Imus, Binakayan, and Perez-Dasmariñas came to be known as Hacienda de Imus.

Various chapters of the Order justified the ownership of the hacienda as necessary support for

their pastoral and missionary activities in the islands of Spain. All the Recollect Seminaries

in Monteagudo (1828), Marcilla (1865) and San Millan de la Congolla (1878) received financial

assistance from the haciendas. Even the expenses of the Comisario General de los Recoletos in

Spain was taken from the produce of the hacienda.

The parcels of land owned by the friars were leased to tenants known as inquilinos. The

inquilino had the duty of clearing, weeding out the tares, and preparing the seedlings, farming

implements, and work animals. They paid the hacenderos 10% of the net harvest called canon, and

the rest remain with the inquilino. The inquilino, in turn, could hire sub-tenants or

share-croppers called casama. The toiling is done by the casama, who would also receive a share

of the produce.

The friar hacienda was under the direct management of a religious priest or a lay brother. The

hacienda administrator who was directly under the provincial of the order had duties of

distributing the land to the tenants collecting rental, setting disputes among tenants, or

transfer the lease when the tenants leave.

In the beginning, the hacienda did not earn much. It suffered even worse setback during the

British invasion of 1762. However, by 1896, financial reports told part of the haciendas were

prosperous. Rice and sugar became major products of the Recollect estates. And as the haciendas

prospered, various infrastructures were built by the best Recollect architects and engineers.

Rice, corn, and sugar became the main crops. Fruit-bearing trees were also abundant.

Friars were, therefore, not only for things of the spirit, they were also gifted in worldly

affairs. Roads linking Imus with the towns of Bacoor, Cavite Viejo, Dasmariñas, and other more

prosperous towns were built. Nineteen bridges were built. The most notable of all is the bridge

in Palico (Imus) known as Puente de Sabel II built by Bro. Matias Carbonel, RSA. For this

project, he was given a medal by Governor General Ramon Monteros. To irrigate the farmland, 54

dams were constructed. There were 28 tunnels, 56 skylights, 38 major canals, and 41 minor canals

to further improve the hacienda.

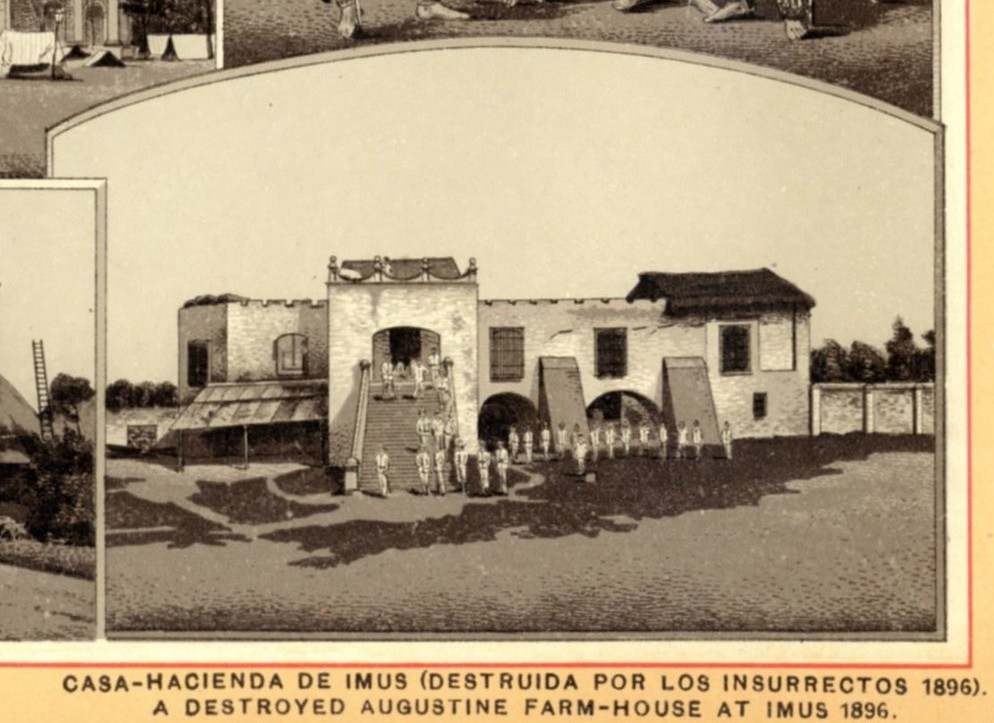

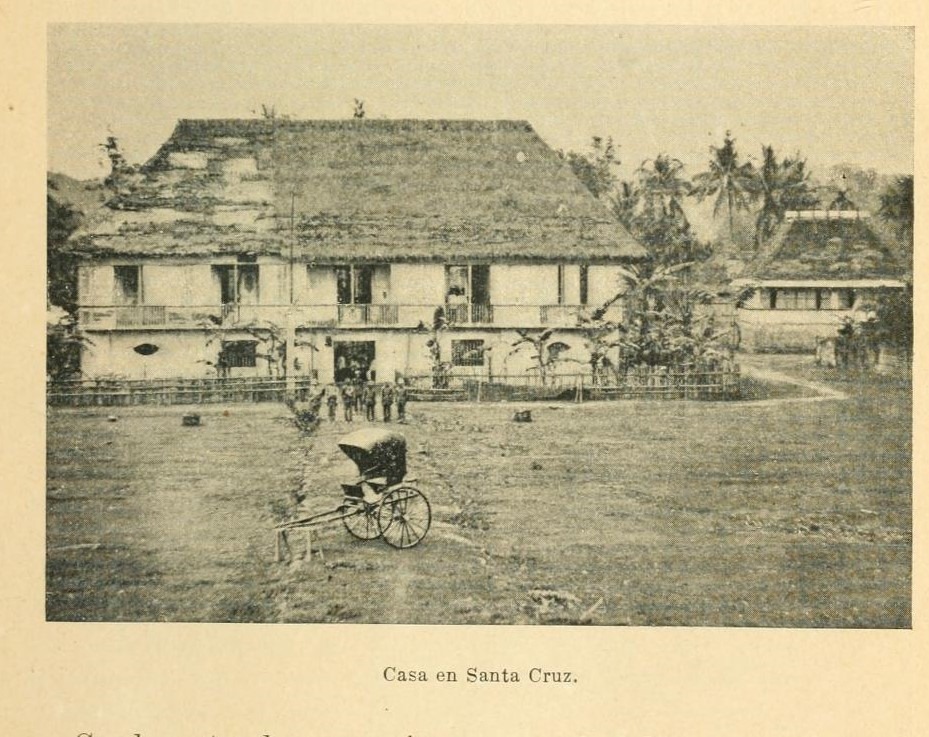

Large casa haciendas, camarins, and almacenes comprised the hacienda complex built in San

Nicolas, Imus, and Salitran in Perez-Dasmariñas. The casa hacienda served as residence of the

friar administrators and his companions. The three canonical communities had their own rectories

with belfry. Among the best Recollect architects and engineers were Lucas de Jesus Maria, ORSA,

Juan de la Virgen, ORSA, Roman Caballero, ORSA, and Hilario Bernal, ORSA.

One of the best remembered friar hacenderos was San Ezequiel Moreno. He was fair and just in

dealing with the workers. He looked after the spiritual wellbeing of the people. Even when he

was no longer in the hacienda, he would always have the people in mind. When an epidemic broke

out, though he was in Las Piñas as parish priest, he went back to Imus to minister the sick in

the hacienda. San Exequiel became Bishop of Pasto in South America. Eventually, his holiness was

recognized by the Church, and he was canonized by Pope John Paul II.

The Jesuits owned haciendas in Silang, Carmona, Maragondon, and Looc (now part of Batangas). In

1695, they also acquired the hacienda of Naic. However, all these would be lost with their

expulsion in 1768.

The Augustinians were the first to arrive in the Philippines, but they owned only a few lands in

Cavite. They acquired the Hacienda de Sta. Cruz de Malabon and Indang in 1720. Then in 1866,

they bought the Hacienda de San Francisco de Malabon from Doña Ysabel Gomez de Cariaga who in

turn bought it from the heirs of Doña Maria Josefa y Ursua, the Condesa de Lizarraga. It was

around 13,000 hectares.

The Haciendas of Tanza and Indang were eventually turned over to the hands of the Dominicans in

1761. In 1831, the Hacienda de San Isidro Labrador of Naic which originally belonged to the

Jesuits was also acquired. Its income was used to support the University of Sto. Tomas.

Even the simpler Hospitaller Congregation of San Juan de Dios acquired some woodland and grazing

land in Leyton (Ligtong), containing several heads of horses and cattle. It supported the

Hospital de San Juan de Dios de Cavite.

From the maladministration of haciendas, conflicts and animosities between friars and tenant

built up. These, sometimes, ended in violent confrontations as in the case of Silang’s agrarian

revolt.

In 1745, an agrarian revolt erupted in Silang. The source of the conflict was a portion of

lowland ricefield in what is now the town of Carmona. The land was temporarily leased to the

Dominicans, but the friars decided to take actual possession and ownership of the said property.

A self-proclaimed General Joseph de la Vega of Silang organized a Militia of 1,500 armed men

from Silang to fight the Dominicans and recover their land. The revolt rapidly spread to nearby

towns and provinces of Laguna and Batangas. After some bloody confrontations, a truce was

proclaimed, and a more peaceful settlement of the conflict was agreed upon.

During the court litigation, the Jesuits acted as defenders of the people of Silang, against the

Dominicans. As a result of this peaceful settlement, the people of Silang, led by Bernabe Javier

and Gervacio de la Cruz, bought the said property from King Ferdinand of Spain for 2,000 Mexican

pesos. This property became a communal land, which would be the subject of a bitter conflict

between its tenant and the past provincial administration of Cavite.

Unfortunately, some of these agrarian protests degenerated into tulisanismo. People who were

oppressed by the friar landlords were driven to the mountains. The friar hacenderos were the

main target of their attacks. However, the attacks became indiscriminate that town folks,

whether rich or poor, became the target of robbery. As Eric J. Jobsbawn said, banditry or

tulisanismo was “little more than peasant protest against oppression and poverty; a cry for

vengeance on the rich and the oppressors.” Cushner, on the other hand, said, “One other response

to Spanish rule in general and to the Spanish land control in particular, which has not yet been

studied is the significant increase in brigands in the late 18th Century.” While this

observation may be true, it cannot also be denied that some groups have been inspired by selfish

motives. Even during the American period, a lot of anti-American groups were lump into the same

category. Hence, Cavite became notorious as the “madre de los ladrones.””

In 1820, Luis Parang and in 1860, Casimiro Camerino would lead the same kind of agrarian revolt

in Imus.

Casimiro Camerino, a peasant leader from Imus, was unjustly labeled as “tulisan” by the Spanish

authorities. When the agrarian unrest resurged in the mid-1860s, Camerino was recognized head of

the peasants, an organized group that went to the hills. His gang of more than 50 men used the

forest of Tampus and Salitran as their hideout. They scattered bamboo traps on the ground as

shown by the basket filled with offensive spiny materials and empty jars of gunpowder found by

Spanish authorities. No wonder that one river in Nancaan, Dasmariñas was called “Pasong Ladron”

(Thief). This river was usually used by the tulisanes.

In 1890, San Roque, Cavite was threatened by a 50-member tulisan band coming from Salitran led

by Jose Espiritu or Joseng Kastilla. Through some connections with the principalia of Imus, the

planned attack on Good Friday night did not materialize.

Though the friar hacendero seemed to be very powerful, he was also strictly accountable to the

prior provincial. Strict accounting and recording of every transaction were imposed. Based on

the report sent to Madrid, a lot of policies were made not only for the benefit of the friars,

but also for the Indios who tilled the land as well.

However, in many cases, what was on paper report was different from what actually happened. The

Recollect Order might have made policies beneficial to the very people they wanted to save, but

the particular conduct of the different friar hacenderos and those who led the work in the

haciendas might have been less humane and Christian. Whether rightly or wrongly perceived, the

maladministration of the friar haciendas was one of the major causes of the revolution in the

Philippines and more particularly in Cavite.

Caviteños were very religious people. This was very well manifested through the way they

conducted themselves during the revolution. Masses and novenas were said not only for the

success of the struggle, but also for the eternal repose of those who lost their lives whether

foe or friend. A very religious Cavite would not have laid its hands on consecrated people like

the friars If not for the mounting grievances that had been stored for centuries. Based on the

report of Recollect casualties, 14 members of the Recollect Order were killed in Cavite at the

height of battle and fury. The parish priest of Perez-Dasmariñas, Fr. Toribio Mateo, Bro. Luis

Garbayo, and Bro. Julian Umbon of the Casa Hacienda de Salitran were killed by the

revolutionaries.

Casa Hacienda de Imus

Casa Hacienda de Imus.jpg

Casa Hacienda de Malabon

Casa Hacienda de Naic

Casa Hacienda de Tejeros - 2